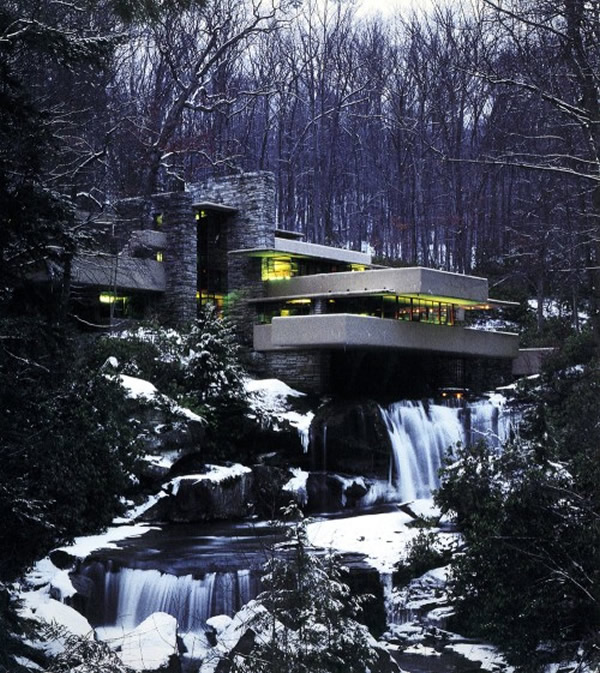

I'm currently reading Fallingwater Rising by Franklin Toker, the 'biography' of the infamous house, and it set me to wonder whether there was there ever a more important private client in the history of modern architecture than Edgar Kaufmann and his wife Liliane?

A successful businessman, owner of a famous Pittsburgh Department Store, EJ Kaufman commissioned some of the best known works of modern architecture, including most famously, Fallingwater, in Bear Run, Pennslyvania, by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Toker book is excellent and detailed in describing how the Kaufmann's and FLW created Fallingwater, but for those short of time, this superb article in the NY Times by Kevin Gray summarises it brilliantly. The history of the Kaufmanns and the drama played out around Fallingwater would make a brilliant film or TV series, as Gray calls it, a Modern Gothic.

The story of how FLW designed Fallingwater is one that never fails to grow in the telling. In one version we see Wright as a blur of activity as assistants rush around feeding him pencils and paper so as not to break the creative fever that gripped him. Our collective love of creation myths (which explains why Hollywood keeps 'rebooting' superhero films), gives the creation of Fallingwater its elevated status. Perhaps it is the idea of creativity ex nihilo, of the form plucked from the ether, or the strive to understand that moment of inspiration, the divine madness of creativity, that draws us to these stories.

The legend grew that Fallingwater was drawn in 2 hours, and that Wright had not committed any ideas to paper before the most famous act of architectural prestidigitation, on September 22, 1935.

The design of Fallingwater had to cope with unusual living arrangements, as Liliane and Edgar had separate bedrooms and led largely separate lives. As first cousins, their marriage was essentially one of convenience rather than love, with EJ's numerous indiscretions paid a heavy toll on Liliane. While at first Fallingwater was a party house where the Kaufmanns made a great show of entertaining the good and the great, Liliane came to find it oppressive, and frequently retreated to the guest house " where she could lounge in solitude and swim in the hillside pool."

After selling the department store in 1946, EJ had little need to stay in PA with its cold dark winters, and instead became spending more time on the west coast. FLW bristled with anger and frustration when EJ Kaufmann commissioned former Wright pupil Richard Neutra to build them a house in Palm Springs, but later, when Liliane, estranged from Edgar, contacted FLW about building a retreat for herself, he never replied. ''He knew who buttered his bread." says Toker.

Things didn't end well at Fallingwater when Liliane Kaufmann died there in 1952 on a rare weekend when both her and EJ stayed there. Was it an accident, and overdose on the sleeping pills she took, or something more sinister? Her ghost is said to still haunt the master bedroom.

The relationship between EJ Kaufmann and Frank Lloyd Wright is a compelling one - they argued furiously over the details of Fallingwater, but each had too much invested in the other to back away. FLW designed over 20 other buildings for Kaufmann, none of which were realised in Kaufmann's lifetime. Frank Lloyd Wright's unbuilt legacy looms large - there are over 500 unrealised designs, almost as much as the built oeuvre. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation seeks to preserver the legacy and oversees any attempts to build any unrealised designs, with 16 projects so far completed with an official "designed by Frank Lloyd Wright" seal of approval.

The Massaro House

One of the many buildings that FLW designed was for a little island on a lake in upstate New York, for a man called Ahmed Chahroudi, in 1950. Chahroudi had boasted to Kaufmann that "When I finish the house on the island, it will surpass your Fallingwater." But he could never afford it, nor a second design FLW produced, an eventually sold the island. A local man, Joe Massaro bought the island in the late 1997 and set about building the house FLW had designed.

This move was not without opposition. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, official custodians of Wright's legacy, refused to give any assistance to help Massaro realise the plans, and argued that they owned the copyright on the plans. But a court ruled that there was no copyright, Massaro owned the island, and with it came the drawings. Eventually the argument was settled that Massaro could only describe the house as "inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright".

Eventually Wright found an architect, Thomas Heinz, willing to help him realise the project, and make it as faithful as possible to the original design. Construction began in 2000, and was near completion in 2006, when the architectural press became aware of it.

It has come in for much criticism as an ersatz Wrightian confection, with Heinz having to interpret Wright's design which consisted of just 5 drawings, a plan, a perspective and 3 elevations. Several modern features were added, such as domed skylights, superseding Wright's details that were considered outdated. Perhaps the most obvious deviation from Wright's style are the rubblestone walls, often referred to as 'desert masonry' which in Wright's designs the stones are closely pack and relatively flush. At the Massaro house the stones are widely spaced and jut out of the concrete, giving the walls a nougat-like appearance. Massaro defends this because of the need to add insulation into the walls, and thinks that Wright would have done the same to meet current building codes. But this is what happens when you build a building out of its time.

While inevitably it lacks the purity of vision that genuine Wright houses possess, it does have the essence of a late period Wright house, with huge cantilevered balconies, the strong horizontal elements countered by the massive vertical walls, the synthesis of the house with its location.

Massaro has put the island up for sale. Even in 2010, only 4 years after completion, Massaro seemed to have turned away from the house. In an echo of Kaufmann's move away to the west coast, Massaro stated "I put my heart and soul into this, but I’m spending more time in Florida now. I’m thinking of building a Frank Lloyd Wright house that he designed for the ocean."

In 2012, the house was advertised widely on the types of website that those looking for private islands would be likely to visit, with one even offering an online shopping cart where you can buy it with a single click for a cool £17 million.

Blueprints

In another interesting development, some blueprints from the original Fallingwater were made available by auction. Bidding ended in September 2012, with a top bid of £22,824. From the auction website, the description is that "the blueprints, which were discovered in Long Island, are accompanied by a letter from architect Arthur Hennighausen which reads: "The shop drawings of the 'Falling Water' steel sash were given to me as a professional courtesy at my architectural office in Waukegan Illinois by J. D. Graff who at that time was sales representative for Hope Windows, Inc. This was in the spring of 1938. No record was kept to further identify the time or place."

While an interesting piece of memorabilia, blueprints of a window detail are not in themselves useful for anyone looking to build their own version of Fallingwater. But this, and the Massaro house, raises a question about ownership and authenticity in architecture. Can a building be copyrighted? And if you own the blueprints to a house, do you own the rights to build that house?

Inevitably in this era of context-free image porn on sites like Dezeen, unscrupulous developers can plunder the archives for more than just inspiration. Zaha Hadid has recently discovered in China that imitation is the highest form of flattery, with her project for Wanging SOHO in Beijing pirated for a development in Chongqing, a 'megacity near the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau'. Thus Hadid finds herself in the position of racing to complete the original project before the copy is finished. It's the sort of thing that would have had Baudrillard in stitches.

The simulation has overtaken the real.