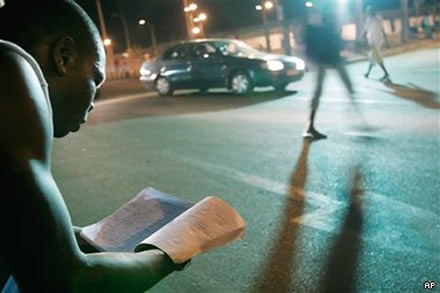

In a syndicated news story by Rukmini Callimachi, (viewable here), we learn that each night, children in Conkary, Guinea head to the car park at G'bessi International airport to study under the floodlights.

It's a tale that illustrates strongly how a dream-myth of globalisation, with an international airport bringing empty promises of prosperity, contrasts with a poverty stricken nation, "ranked 160th out of 177 on the United Nations' development index", where only a fifth of Guineans have access to electricity, and power cuts are frequent. But the counterpoint is the resourcefulness of the children, desperate to gain an education, and what William Gibson would call "the street finds its own use for things". A concrete bollard becomes literally a seat of learning, a floodlit car park transformed into a vast study hall, with it's own spatial hierachy:

"They sit by age group with 7-, 8- and 9-year-olds on a curb in a traffic island and teenagers on the concrete pilings flanking the national and international terminals. There are few cars to disturb their studies."

Elsewhere across Guinea, students have to study at gas stations, or crouch on the curbs outside the homes of wealthy families.

"'We have an edge because we live near the airport,' says 22-year-old Ismael Diallo, a university student."

Meanwhile the precious, fragile nature of electricity in Guinea highlights the ubiquitous excess of energy that is consumed in the West.

"According to U.N. data, the average Guinean consumes 89 kilowatt-hours per year — the equivalent to keeping a 60-watt light bulb burning for two months — while the typical American burns up about 158 times that much."

Recent power outages in San Francisco in the US or water shortages in Gloucestershire in the UK are seen as outrageous affronts to our civility. Taking electricity and other utilities for granted makes us forget how privileged we are.