Earlier this year, Floating Worlds and Future Cities, an exhibition and symposium in New York, brought into focus the largely forgotten figure of Lazar Khidekel, and sought to place him properly as one of the pioneers of Suprematism. Khidekel could even be considered the first Suprematist architect, and was instrumental in helping Suprematism move beyond painting towards built form, urbanism and cosmic civilisation.

Khidekel was just 14 years old when admitted to the Vitebsk school of art, under Marc Chagall. In 1919, Kasmir Malevich founded a group called UNOVIS - Champions of the New Art - which also included El Lissitsky, Nina Kogan, Nikolai Suetin and Ilya Chashnik as well as Khidekel.

In 1921, (at the age of 17!) together with Ilya Chashnik, Khidekel headed the architecture and technical department at Vitebsk School of Art, and set about implementing a radical curriculum.

"The training of architects who at the same time will be the organisers and designers of the architectural units of the blocks that will constitute the streets and cities; the training of architects who will also be able to design and plan the economic centers."

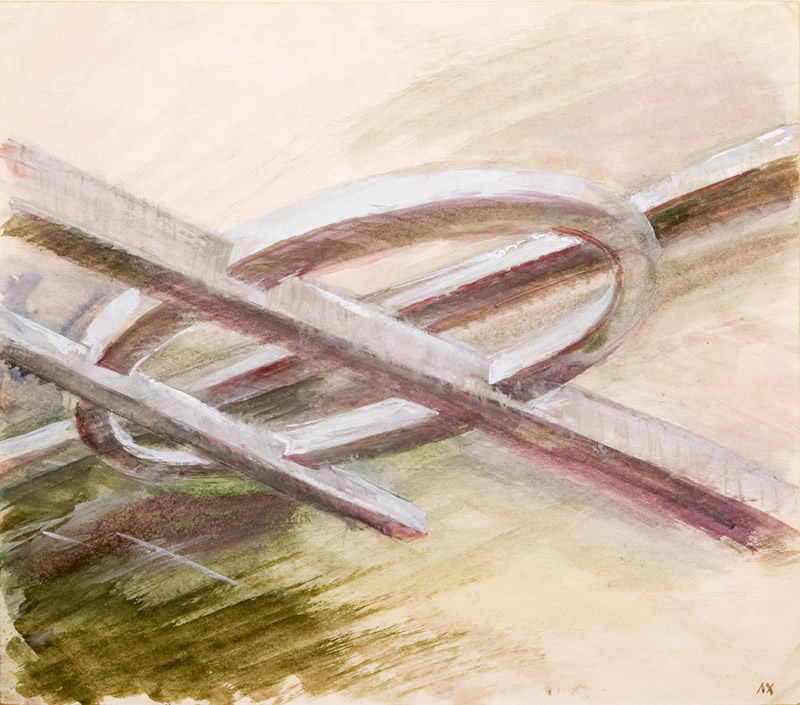

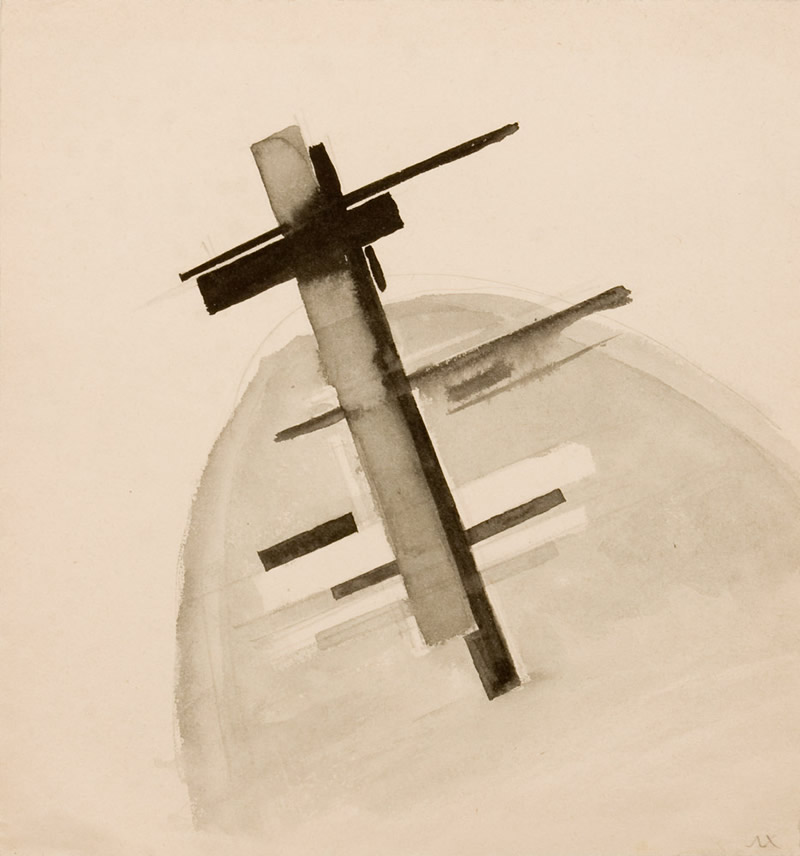

The official website at www.lazarkhidekel.com offers a tantalising glimpse of Khidekel's talents. The Suprematist works are drawings or paintings on paper, and lack the polish of finished works by Malevich or Ilya Chashnik, but are formally just as stunning.

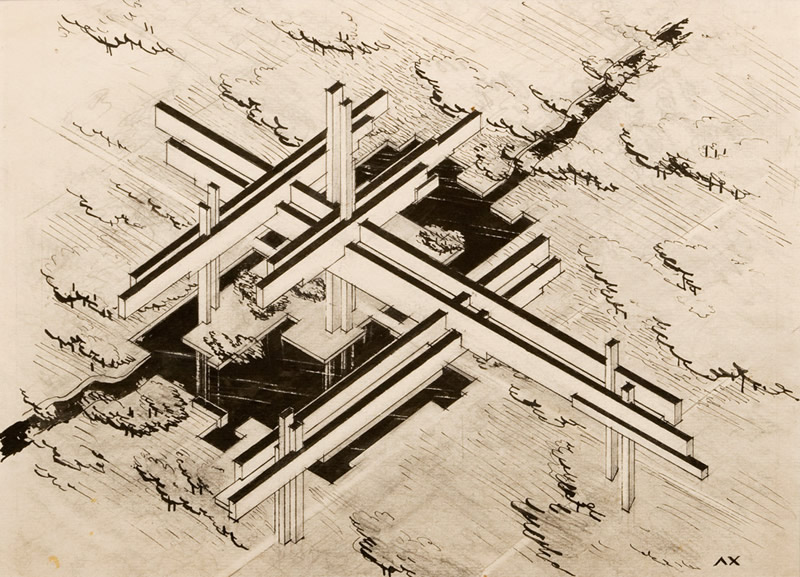

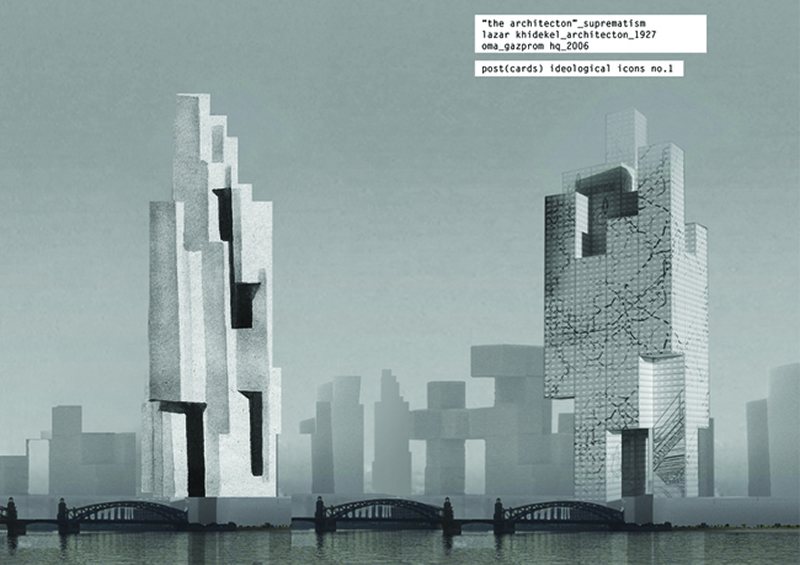

But it is in the architectonic works that we see Khidekel's unique talent, in translating the essence of Suprematist composition to architectural forms. His Architectons matched Malevich's own sculptural explorations, but Khidekel also went further in designing projects meant to be built, such as the Aeroclub project of 1922. As well as practical architectural projects, Khidekel continued to dream of floating cities and futurist visions of space and form. Malevich had called for his students "to show the entire development of volumetric Suprematism in accordance with the sensation of the aerial (aero) type and dynamic", and Khidekel responded with his designs for Aerograd, a city on stilts, hovering above water.

Arguably, only Gustav Klutsis with his designs for a Dynamic City was operating in the same raridied atmossphere, of a cosmic reach for architecture breaking free from the Earth.

Later, at the architectural college in Petrograd, Khidekel continued to develop his architectural ideas to more practical applications, as well as working with Malevich, Suetin and Chashnik to create Architectons and Planits.

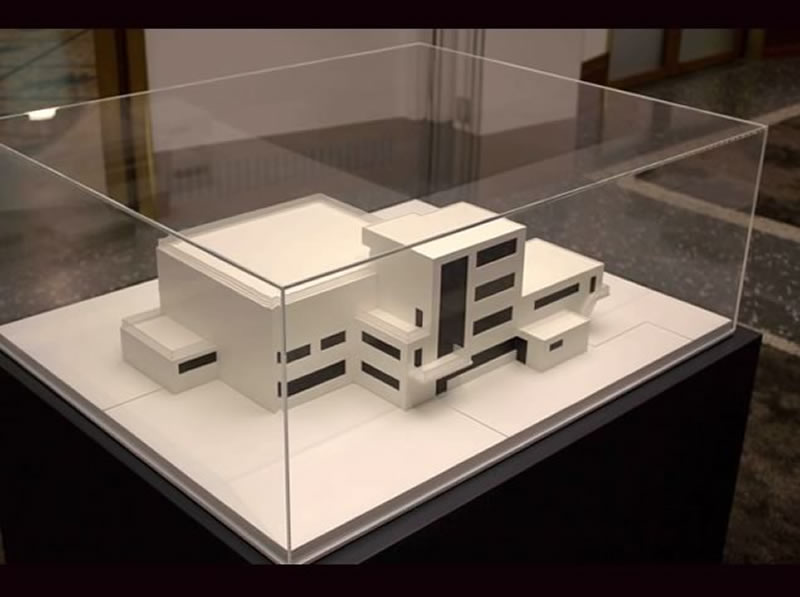

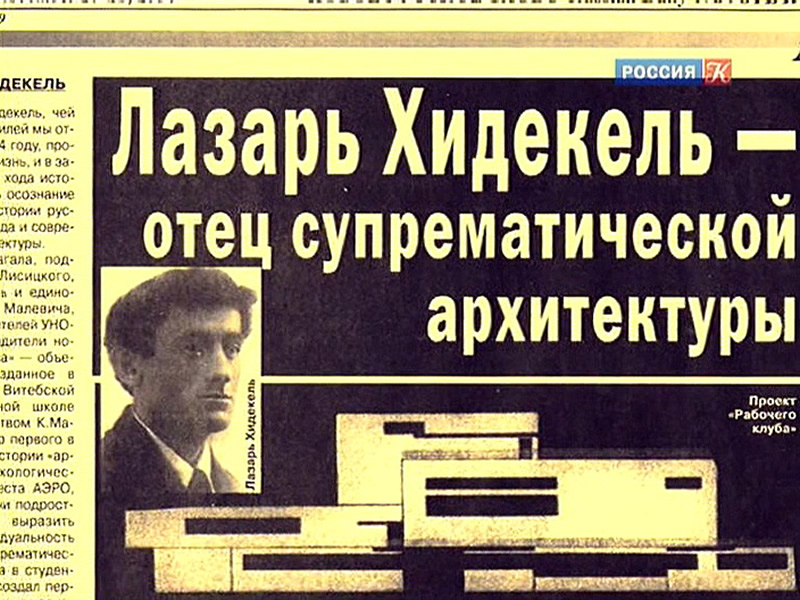

In 1926 Khidekel created the first realised Suprematist built form, a Workers Club. It was originally credited to Malevich and published in Berlin. A restrained piece of modernism, it is reminiscent of similar avant grade designs of the Bauhaus or De Stijl architects such as Rietveld or JJP Oud.

In later years Khidekel continued to work on architectural projects, while continuing to create visionary drawings of structures and cities hovering just above the landscape, or orbiting the earth in space.

As Charlotte Douglas noted (quoted in Regina Khidekel's essay "The Trajectory of Suprematism":

"Khidekel’s distinction was that this initial vision of Suprematist structures floating in space remained a central part of his art and architecture for the next forty years, and richly informed his later development as a professional architect."

It is not surprising that architects and designers are beginning to rediscover Khidekel's and recognise his visionary works as prefiguring many later projects. In the article "Discovering Khidekel" by WAI Architectural Think Tank, Khidekel is dubbed "The Last Suprematist", still prone to dizzying spatial visions long after his peers and Suprematist mentor Malevich had retreated to a less utopian position.

"With each brushstroke of watercolor the Bolshevik utopia of utilitarian icons was painted obsolete. With the elongated appearance of each monochromatic volume a new form of revolution was achieved. Khidekel architectural visions transcended the rhetorical games of the revolution by developing complete cities out of sublime architecture. Long before Friedman’s Architecture Mobile, Constant’s New Babylon, and Isozaki’s Clusters in the Air, Khidekel imagined a world of horizontal skyscrapers that through their Suprematist weightless dynamism seemed to float ad infinitum across the surface of earth."

While the city hovering above the ground still remains a powerful trope in both science fiction and architectural fantasy, Khidekel's visions still manage to look futuristic, arguably more so than most of the Metabolists or Situationist projects that today feel retro-futurist, inextricably tied to the past.

Khidekel's work remains endlessly floating towards the future.