In the first post about Georgii Krutikov's City of the Future project of 1928, we looked at his proposal for a floating city, freed from gravity, a paraboloid 'gleaming thimble’ soaring up into the air. But for all of Krutikov’s interest in mobile architecture, the city was essentially static, suspended above a manufacturing and industrial zone on the surface of the earth.

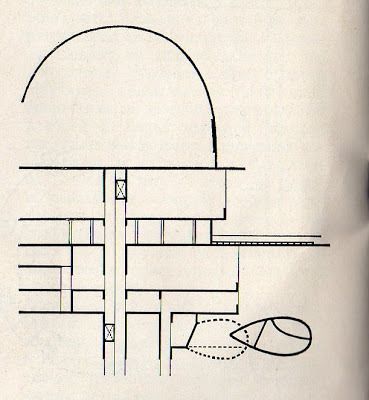

But if the new forms of the city were floating, connection between the aerial parts was facilitated by flying ‘cabins’, capable of travelling from the dwelling units of the residential blocks to other units within the same city; to the ground; or to other floating cities.

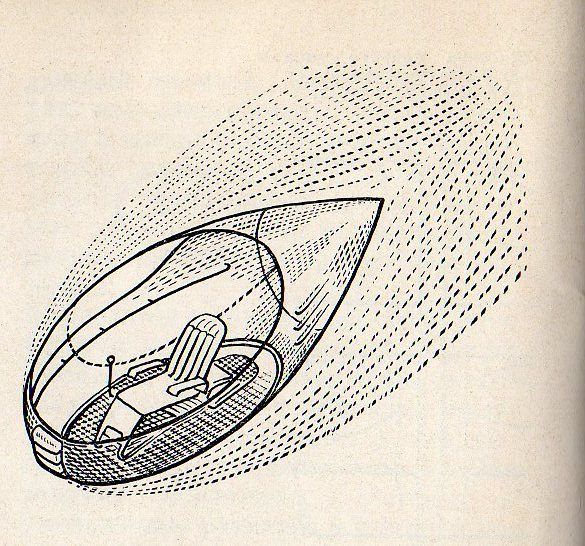

The teardrop design prefigured Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion car, though without wings it would have been totally unstable. Like the rest of the flying city proposal, there is no indication of how the car flies – how it moves, what powers it, or how it is controlled other than a slender joystick. As a pure utopian vision, Krutikov had little time for details or practicalities.

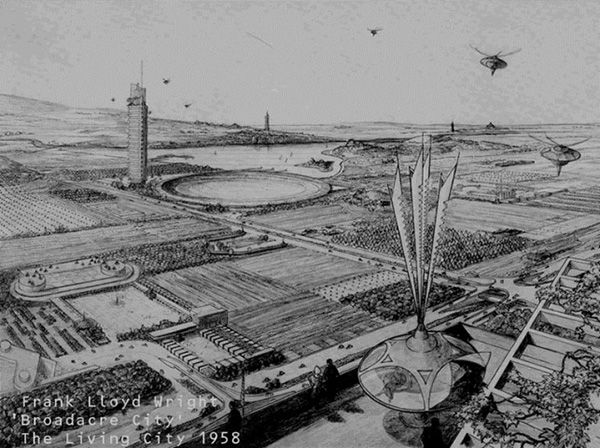

The flying cabins of Krutikov's floating city are also redolent of the gyrocopters of Frank Lloyd Wright's Broadacre City, first presented in 1932, but which pre-occupied him for the rest of his life. They also perform a similar role, connecting the disparate elements of a disurbanist city.

From Floating City to Skycar City

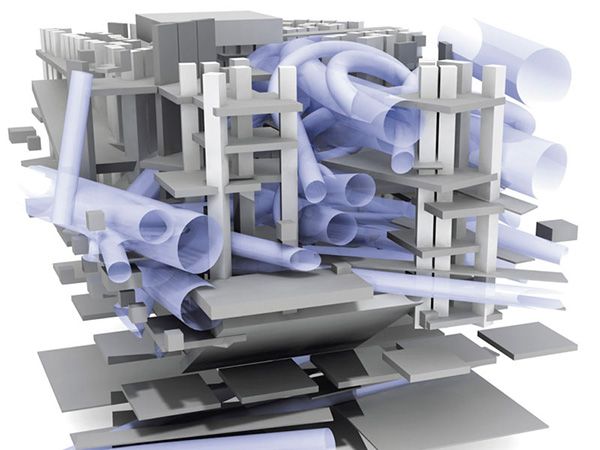

The Dutch practice MVRDV spent some time pre-occupied by the urban possibilities or flying vehicles, and in 2007 published the book Skycar City, based on a design studio conducted with students at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Architecture and Urban Planning. In it, not only are typologies of flying cars explored, but also how a city might be reconfigured based on the spatial freedoms and velocities that the skycars offer.

Further investigations consider parking typologies, city typologies, and inter-city connections. MVRDV, in much of their research projects have taken trends and pushed them as far as then can, as design provocations, and Skycar City is no exception.

“liberated from the confines of the groundplane, the advantages and potentials of a sky-based circulation infrastructure transforms the notion of commuting and moving throughout the city. This paradigm shift also utterly revamps the way in which our cities evolve and grow."

MVRDV’s programmatic approach to design leads them to create 4 archetypes of Skycar City: The Tower City, The Swiss Cheese City, The Coral City and The Garden City, based on a hypothetical city of 5 million inhabitants. Each type has a different approach for the relationship between ‘program’ and ‘pathway’, i.e. built form and network connections, taken to its logical conclusion.

It’s a fascinating book, much more interesting for its urban speculations than its Skkycar designs, MVRDV, like Krutikov and FLW before them, understand that personalised aeronautical vehicles, have the ability to transform society and space.

The term skycar was first coined by the Canadian engineer Paul Moller, who has spent the last 50 years developing a personal VTOL vehicle, with limited success. The latest model, the M400, which can seat 4 people, has so far demonstrated a tethered hovering rather than free flight. Moller's designs are based around 2 or 4 prop engines, housed in a rotating nacelle that can be directed vertically for VTOL and horizontally for conventional flight. Meanwhile, advances in drone technology have developed to a point where they are able to transport a person, with models such as the Ehang 184 working and in use, albeit with a limited range and loading capacity.

As with conventional cars, an abundance of personal vehicles creates issues of parking whenever drivers wish to become pedestrians. Skycar City imagines new typologies for parking structures and even 3-dimensional variations of the drive-in entertainment complex. While Krutikov imagines how the ‘cabins’ detach from the floating habitation units to fly down to earth, there is no consideration of how parking is managed once down on the surface.

Sky-high rush-hour

MVRDV’s explorations of a Skycar City do no consider the notion of anything other than the personal ownership of the skycar: there is no consideration of shared ownership or a ubiquitous taxi service such as Uber. Neither does it consider anything other than spatial separation of home, work and leisure places, with the Skycar as the connecting transport. In Skycar City we will all still commute, pushing our traffic jams and rush hour skywards.

Are the days of owner-drivers over? Uber, Lyft, ride-sharing services such as BlaBlaCar and Via, and self-driving cars might not only enable new modes of personal transportation and shared transport, but could have huge impacts on urban design and transport infrastructure. Flying cars might be another step further. Indeed, Uber themselves are already looking beyond wheeled vehicles to flying cars, having recently hired a NASA engineer to head Uber Elevate, while Google are investing in startups to develop VTOL cars.

There is no doubt that skycars could refigure entirely the layout and infrastructure of the modern city. Making city blocks themselves float, as Kruitikov imagined, might take a few more technological leaps. But his vision might yet take flight.