"I like Nike, but wait a minute.

The neighbourhood supports, so put some money in it."

- Public Enemy, Shut Em Down

In the 18 years since Chuck D rapped those lines, Nike has moved far ahead of the curve in developing an advanced urban marketing strategy that seeks to connect their brand with neighbourhoods in cities across the world.

In a prior post, Branding the Boroughs, I mentioned the Nike Scorpion KO campaign as a example of marketeers refiguring the city in terms of their brand. Via the web site of creatives Denesh and Anuj I've finally been able to find some more images of it.

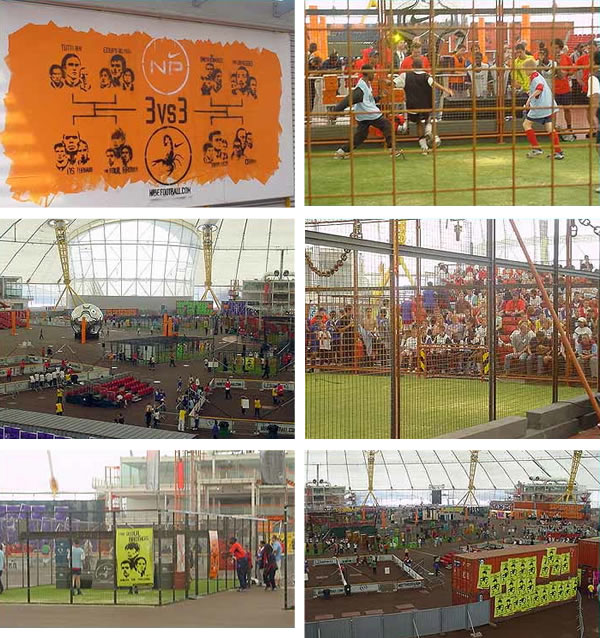

The 2002 Scorpion KO campaign was centred around a cage-soccer tournament of 3-a-side, first-goal wins, an extension of a TV advert, directed by Terry Gilliam, and fronted by Eric Cantona.

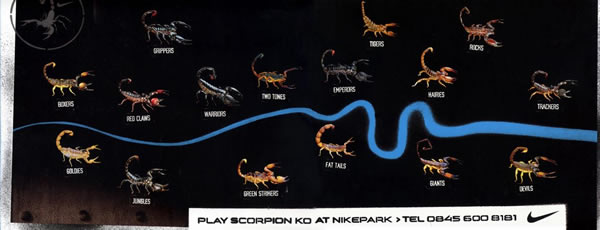

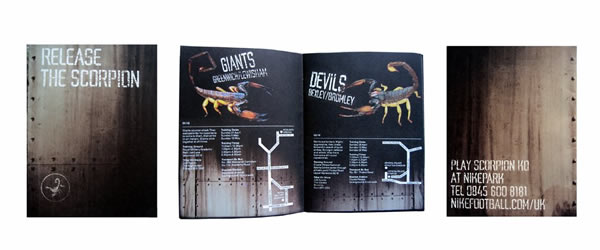

Teams across London competed in a number of regional heats (at venues rebranded Nikeparks) before competing in a final at a rebranded Millennium Dome (Nikepark @ the Dome). The campaign was 'taken' to the streets of London by giving each borough in London the identity of a species of scorpion, eg Greewich Giants, Bexley Devils, Enfield Tigers, each with its own signature moves, style of attack etc, and complete with text message/ sig file icons. This was then reinforced via traditional outdoor advertising - bus shelters and billboards, with more guerilla forms such as stencil graffiti/ flyposting, adding an edgy ("you are now in Emperors' territory") mythological layer across the city.

In connecting young people with an urban identity reinforced on the streets, and via online and mobile messaging, Nike created a powerful way of representing the city both with space and with signs, a 'Situationist' urban realm.

According to the Wikipedia page:

"Following the airing of the commercials, in June 2002 an estimated 1 to 2 million children competed in matches following the Scorpion KO rules in about a dozen cities worldwide, including London (in the Millennium Dome), Beijing, and Buenos Aires.

Nike considered the campaign a success, with Nike president Mark Parker commenting, "This spring's integrated football marketing initiative was the most comprehensive and successful global campaign ever executed by Nike."'

In his book 'Who's afraid of Niketown', author Friedrich Von Borries explores the lengths to which Nike go to transform urban space into brand space. Bart Lootsma, in his preface, writes:

"The new brand city described by Borries ... is a dynamic city, a setting for organizing 'situations.' In order to reach even the smallest target groups, the media will be deployed in this city far more interactively than they are today. Streets, fallow zones, interstitial spaces and ruins will play essential roles in the brand name city. These spaces will not be overlaid with advertising in classical fashion, but will instead become the objects of discriminating marketing strategies. Here initiatives from below that devise new leisure activities will be instrumentalized, as will critical actions and political demonstrations."

Borries considers the role of architecture in the 'brand city':

"In recent years the actual task of architecture has changed radically. The illusion machine of marketing has rediscovered the reality: architecture is now intended to convey the identity of a brand, is now expected, as an experiential realm, to be an element in brand communication."

Though focussed on Nike's activities in Berlin, almost identical campaigns have run in other cities across the world, including London, with events such as North versus South runs, recoding the city as a competitive space, with clearly defined winners and losers.

Borries continues:

"is it the future of the city to be the remix of an advertising spot? The brand makes the space available in which our social relations are mirrored. With Nike, this is the image of the combative city, of a remorseless battlefield of identity. The city reproduces and elucidates our competitive society. Only as an explanatory model can this advertising-becomes-space reach its target group... In the future experience-oriented city, the brand is a crucial agent, if not the paramount one. In that city, the brand becomes a partner in all forms of planning, the determinant of development trends. Precisely to the degree that economic decisions replace political ones, the brand displaces the primacy of the political in the shaping of the city. Niketown is not called that simply because it is a department store for sporting goods, but instead because Nike claims to transform the city it inhabits into a Nike city."

We have as much to learn from Nike as Venturi, from Niketown as Levittown.

Previously: