As the Curiousity mission to Mars nears the Red Planet, another venture, Mars One, aims to build a permanent settled colony on Mars by 2023. They make it sound so easy. But landing on Mars has always been anything but easy.

The key concept of the Mars One project is that, by not trying to return from Mars, it instantly solves all the problems about escaping Mars' gravity well. It's a one way ticket for settlers, never to return. Whilst Elton tells us that "Mars ain't no place to raise your kids", the brains behind Mars One expect there to be no shortage of volunteers to start a new life in the off world colonies. The project creators seem to think that media interest will generate income in the ultimate reality TV show - "Big Brother will pale in comparison". But the Apollo mission should serve as a warning here. Whilst an estimated half a billion people watched Neil Armstrong take the first steps on the Moon, by the time of the last Apollo mission, Apollo 17, just 3 years later, TV audiences had grown bored of watching astronauts prancing around on the lunar surface.

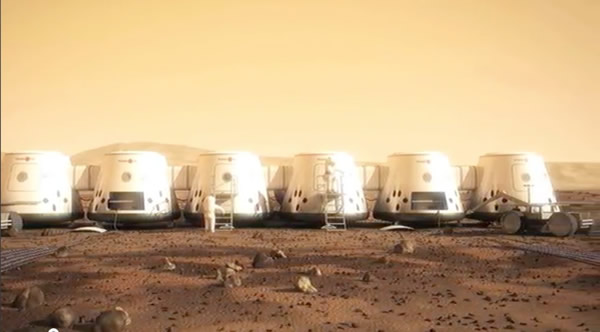

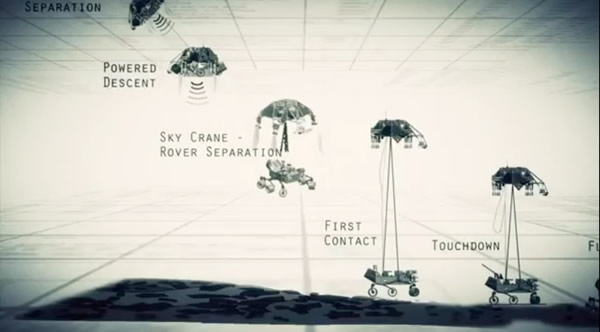

Watching the CGI footage of craft gently touching down, in a neatly arranged row, it seems they have grossly underestimated just how difficult it will be to land on Mars. In this super-slick video, the scientists at NASA behind the Curiousity mission, describe the 7 minutes of terror during which it will be impossible to determine whether Curiousity has made it or not. The rather hubristic video shows the solution to slow Curiousity down to a speed upon which it can deposit the rover gently, a process utilising atmospheric braking, parachutes and retro-rockets.

Mars has just enough atmosphere to create a problem, but not really enough to provide enough atmospheric braking enable a glider-like approach that the Space Shuttle used to return to Earth. The thin atmosphere also means that parachutes will not be as effective as on Earth, and there is no large body of water in which to splashdown. Unlike the Moon, the gravitational pull of Mars is enough to generate considerable acceleration of vehicles towards it. For any return trip, the lander will need to carry enough fuel to lift off again, which will increase its weight and make it even harder to land. At least Mars One doesn't have this consideration.

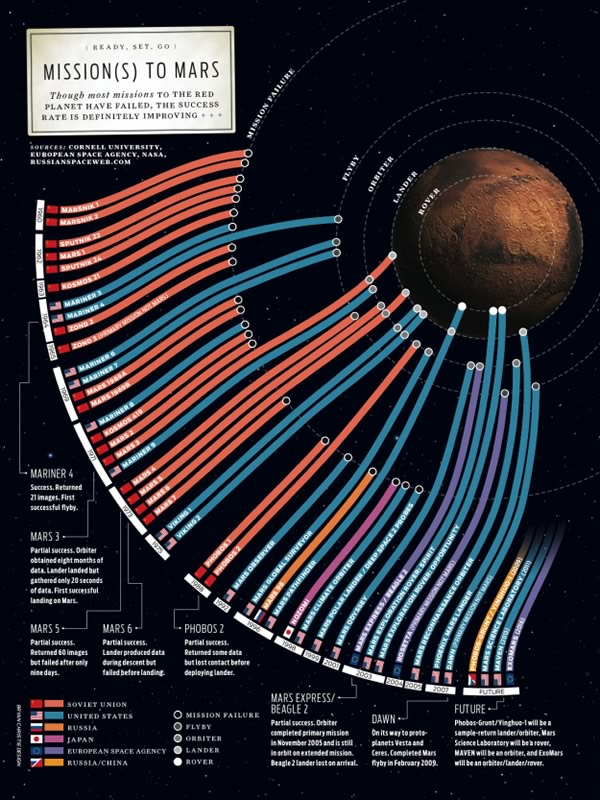

As this chart by Bryan Christie Designs shows, previous missions have a low success rate., often referred to as the Martian Curse.

Mars One is not the only privately backed project looking to get people to move to Mars. Elon Musk, the founder of SpaceX, which managed to send an unmanned vessel to the ISS earlier in 2012, also thinks that a manned Mars mission will be not big deal. Musk figures he needs to get the cost down to $500,000 per person:

'"roughly the cost of a middle-class house in California.” Why that price point? Musk imagines that then, "enough people would choose to sell all their stuff and move to Mars."'

But apart from the price-point, not much seems to have been determined other than some vague assertions that that everything will need to be reusable to make it economic, and that the fuel for the return journey must be available on Mars itself:

""My vision is for a fully reusable rocket transport system between Earth and Mars that is able to re-fuel on Mars - this is very important - so you don't have to carry the return fuel when you go there"

Musk's thinking doesn't seem to have got any further than Wernher von Braun, who conceived his Marsprojekt as early as 1946, and refined it almost continuously over the next 23 years, including a program made for Disney in 1957. On screen von Braun, a showman as much as a scientist, makes an elegant, considered proposal for a manned voyage to Mars. These proposals are even more remarkable given that no-one had even placed any craft in orbit.

Inevitably, von Braun's counterpart in the Soviet space program, Sergei Korolev, also harboured plans to go to Mars, and in 1960, gained permission from the Kremlin to forge ahead with proposals for both manned and unmanned interplanetary missions. In 1960, 2 attempts were made to launch probes to Mars, in the Marsnik program. In 1962, the Mars 1 probe was launched, but only to within approximately 190,000 km from Mars before resuming a heliocentric orbit. The Mars 2 and Mars 3 probes did at least reach Mars. in 1971 but their descent modules malfunctioned either on descent or shortly after landing on the Martian surface.

Most people think of the American Viking landers as the first craft to land on Mars, but they were not. Mars 3 landed successfully on the surface of the Red Planet in 1971, but only managed to broadcast less than 20 seconds of data back to Earth, including the first photograph of the planet's surface, before a malfunction occurred, or a dust-storm destroyed some of the equipment. It would be another 5 years before Vikings 1 and 2 would send back extensive data and colour images of the Martian landscape.

In 1973, the Mars 4 and Mars 5 probes both achieved orbit of Mars, but did not included descent modules. From then on, the 'Martian Curse' seems to have taken hold of the Soviet space program. In 1973, Mars 6 did crash-land a descent module on the surface but was able to transmit data during the descent. The Mars 7 probe reached Mars in 1974 but the lander separated prematurely and missed the surface of the planet.

It was another 15 years before the Soviet Union attempted to reach Mars or its moons again. The Phobos 1 and 2 probes were planned in the 1970s but finally launched in 1989, designed to collect soil from Phobos and gather extensive data on Mars. However, neither spacecraft made it to Mars.

In 1996 another probe, the Mars 96 spacecraft failed to achieve orbit. And of course earlier this year the Phobos-Grunt vessel failed to exit Earth's orbit.

Korolev's plans for manned missions were as ambitious as they were impractical. Unlike the cautious US approach of small incremental steps, re-iterating and refining, the Soviet approach to spaceflight was to think on the grand scale, and try to turn dreams into reality by sheer force of will. The history of Soviet rocketry is full of grand visions and a long list of heroic failures, punctuated by the odd genuine success. In this aspect the Soviet space program mirrored many other facets of Soviet society.

Korolev's 1960 plan was suitably grandiose:

"According to Korolev, the manned expedition on the surface of the planet would include 3 or 4 spacecraft flying in formation. The crew, returning from the surface of the planet, was expected to dock with one of the backup ships, which would be then used for the flight back to Earth"

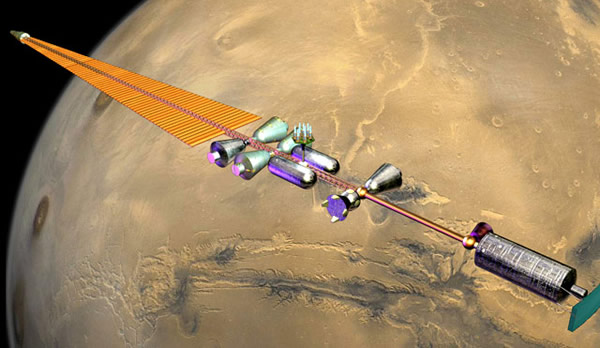

The plan evolved further to become a Martian 'train", five moveable platforms that could traverse the Martian surface, from pole to pole, gathering samples and data:

"One platform would carry the crew cabin with a manipulator and a device for drilling soil. The second platform would be a launch pad for an aircraft capable of flying in the Martian atmosphere. Two more platforms would carry main and backup return rockets, which would allow the crew to take off from Mars.

Finally, the fifth platform would be equipped with a nuclear-powered generator, which would supply the expedition with energy. The "train" would travel across the Martian terrain for a year, collecting samples and relaying data to the base craft orbiting the Red Planet.

At the end of the mission, the crew would take off from the surface to rendezvous with the orbiting base ship for the return journey home."

Planning for manned missions to Mars gained new impetus in the Soviet Union following the success of the Apollo program in landing Americans on the moon. Once the Stars and Stripes had been planted on the surface of the Sea of Tranquility, Soviet ambitions turned away from the Moon and looked with renewed vigour towards Venus and Mars.

Manned Mars mission proposals cropped up again in 1969, 1987, 1989 and 1999. The 1969 project looked to develop a general purpose interplanetary rocket, based around the N1M nuclear powered launch vehicle,a modified version of the massive N1, the Soviet rival to the Saturn V rocket.

The 1988 project was based around using a space station such as Mir as an orbiting ship-yard. The rocketry would place into Earth orbit all the constituent parts to create the fleet of craft to travel to Mars. The space station was to be used as an assembly point to build the vessels that would make the 9 month trip to Mars.

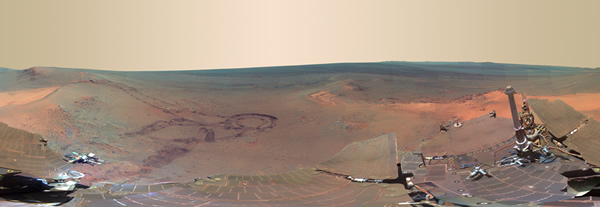

But what will men do on Mars? Recently released by NASA is an amazing panorama of the surface of Mars, stitched together from over 800 photos taken from the Opportunity rover, which has been wandering around the planet since 2004. If you needed any more convincing of the crushing loneliness of being stuck on Mars, it is traced out in the wheel tracks of the Opportunity rover, patiently toiling on its mission, much like the last remaining robot in Silent Running.

Previously