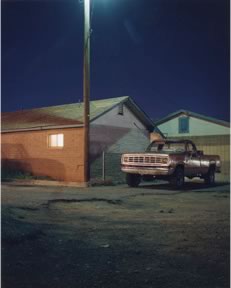

Few things capture the ambivalence of urbanity better than nighttime photography. Contemporary nocturnes continue to explore new ways of capturing the urban condition.

Bright lights illuminate an empty car park. A lone shopping cart provides further dislocation. Elsewhere, a delicate tracery of lights depict the urban boundaries. Next, a row of suburban houses, one with a solitary light on, burning bright deep into the night.

Nocturnal photography speaks powerfully about the banality at the edges of urbanity, the transient nature of human activity, but also about a primal fear of the dark, pushing back the darkness, man triumphing over nature.

People are almost never present in these images, but their mark is everywhere, in the parked car, the office bright with fluorescent strip lights, or the trail of taillights forming ribbons of light. Every picutre is about someone who has left. The photographer is the only referent in these images, stationary to enable the long exposures, let enough light onto the back of the camera to register an image and fix the moment.

The first photographer whos nightwork captured my imagination was Rut Blees Luxemberg, with her book London, A Modern Project. (Amazon.co.uk) Here, the interstitial spaces between roads, buildings are penetrated by points of light, illuminating a sports pitch, a car park, a wasteland - the interzones of the urban fabric. Elsewhere the few lights on in tower block indicate a restlessness, an unseen late-night waker, perhaps a security 'nitelite', or perhaps a careless leaving of the light on.

In the introduction to her article Nocturnes, from the magazine Contemporary, Sarah Thornton traces the origins of the Nocturnes, from music to photography.

"Although a number of eighteenth century composers wrote 'nocturnes', Chopin's slow piano pices popularised the form in the nineteenth. A nocturne was a composition intended to evoke the unsettling beauty of the night, and closely associated with a 'serenade' (which means 'evening music'). But while a serenade is a love song with the certainty and commitment of a vocal declaration, nocturnes are always conflicted. They are elusive and ambivalent, at once haopy and sad, passionate and restrained."

The earliest urban nocturnes were essentially nighttime studies of scenes that might have also been photographed during daylight, under traditional notions of aesthetic beauty. It is only more recently that photographers have turned their lenses on the banal, notionaly dead empty spaces, exploring a new aesthetic, and further emphasising the dislocation and sense of separation.

Part of the sense of disquiet an unease many of these images possess may be due to the huge increase in streelightiing and security lighting now in place, so much that there's barely a patch of ground that isn't bathed in the warming glow of sodium of halogen. Is it paranoia, or are we simply afraid of the dark?

Sarah Thornton again:

"What distinguishes nocturnes more than anything else is the curious way in which they offer relief from the daytime world of acceptable behaviour, official truths and mundane points of view. For me, the antipathy of light and dark has never been about good and evil, but fact and fiction, objectiviry and subjectivity. With nocturnes, one can escape into a shadowy world where the selective glow of man-made lights picks out and interrogates what really matters. Nocturnes share secrets, revel in the uncanny, and allow the repressed to raise its intriguing head. Whether they are therapeutic of threatening, serene of surreal, they always harbour an infatuation with the unsettling beauty of the night."

American photographer, Todd Hido, has made a series of photographs of houses at night, exploring the insecurities of hte suburban condition. As Luc Sante notes in the intro to a Hido monograph, Outskirts:

".. the suburbs are the tundra, and at night the effect is doubled. The suburbs at night are what you see from the window of the plane: chains of light, some of them in patterns like a diagram, some of them too bright, some of them as diffuse as if underwater, all surrounded by nothingness."

Sante continues:

"Todd Hido finds the poetry in the that strangeness, which consists of all the matter implied but unsaid in the margins of thrillers. It lurks in the high-tension wires, the high-intensity lights, the leafless trees and ambitious weeds, the hurricane fences and concrete knee-walls, the red sky of light pollution. If in these pictures it is forever midnight and you are forever stranded and chilled and at a loss."

The archtypal Hido image in these series is of a detached house, with one solitary light, burning deep into the night, a restless unquiet rather than a peaceful sleep.

Elsewhere, British photographer Dan Holdsworth captures more urban concerns, such as a 1999 series entitled A Machine for Living, featuring empty nocturnal car parks, overexposed with a forest of high-intensity street-lights.

In the Megalith series, one of which is featured on the cover of the recent monograph, (Amazon UK) large freestanding structures, a control tower or a roadside billboard blurt light into an empty void.

Holdsworth is fascinated with what he calls this "inter-liminal" spaces and in-between forms, mapping hybrid spaces that blur the boundaries towards previously polar oppositions: rural/urban, wilderness/civilisation, natural/artificial, first world/third world.

In the Autopia series, where Holdsworth gaze lingers over the banality of empty car parks, the duality is set up between the still, empty zones pictured, and the frenzied activity of these space in daytime.

In the city-scapes of Florian Maier-Aichen, predominantly of LA, depict an urbanscape like a jewelled carpet, tucking into a photographic tradition from Gursky and Doug Aitken, but also of a scenic tradition of Blade Runner and film noir. We are left to imagine our own stories in the thousands of points of lights below.

There are many other photographers exploring this strand of disquieting nighttime photography, and there are web sites dedicated to nighttime photography techniques such as www.thenocturnes.com, but few photographers have made it the focus of their work in the way that Luxemberg, Hido and Holdsworth have. The city becomes sculpture.

From the introduction to Rut Blees Luxemberg's "London, a Modern Project", by MIchael Bracewell:

"It is on the extreme edge of the urban condition - hanging in space or witnessing urban services which appear to have nothing to serve - that the city which we work within reconverts into a sculptural form whose function, like the febrile light with which Rut Blees Luxemberg's photographs are suffused, is a reality rendered artificial in the brief suspension of time".

[first published 19th April 2006]