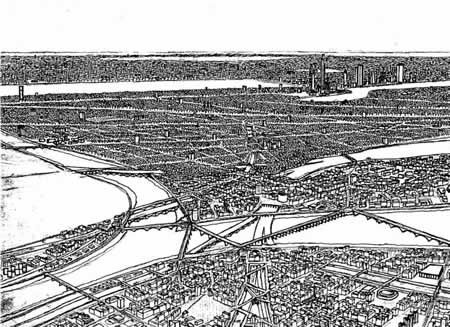

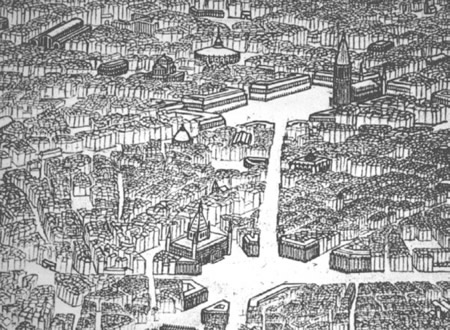

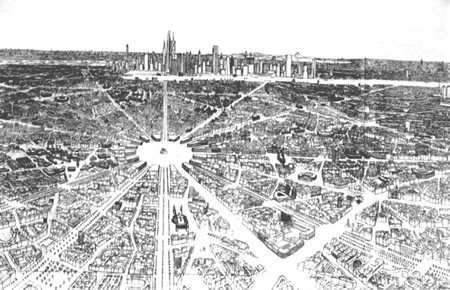

The city of Urville, population just under 12 million, lying on a Mediteranean island just off the coast of Cannes, has been lovingly described in minute detail by Gilles Trehin. In his book, entitled simply Urville, Trehin's detailed illustrations and renderings depict the layout of squares, major space, and suburban sprawl, redolent of 18th Century Paris. The influence of French urban patterns is strong, and a certain Hausmanisation also seems to have taken place at some point in Urville's history.

Urville, is of course, a fictitious city, existing only in the head of Gilles Trehin, but for him it is palpably real. An autistic, Trehin has been working obsessively on the city-planning, urban history, and geogrpahy since childhood, like a paper and pencil version of Sim City.

But it is not just autistic savants who dream of building whole new cities, it is something they share with the scores of architects who have dreamed of building utopian communities in their own idiom. With its precise pencil renderings, Urville is strongly reminiscent of Sant'Elia's La Citta Nuova, and Frank Lloyd Wright's Broadacre City.

But implicit within an architect's utopian vision of a new way of living is a critique of current society and current urbanism, whereas Urville simply is. Almost a defining trope of autism is an inability to empathise or understand social structures, and Urville is in no way presented as an alternative society any more than someone's SimCity creation. Unlike Broadacre City, which was probably as close as FLW got to socialism, though he never came out an said it. Broadacre City is fiercely anti-urban, anti-industrialist, instead a continuous suburb, a bucolic paradise where everyone would own an acre of land, and the speed of a motor car determines the frequency of local markets. We never see the factories where the cars are manufactured, nor the flying helicopters Wright peppers around to try and inject some much need futurism into the mise-en-scene.

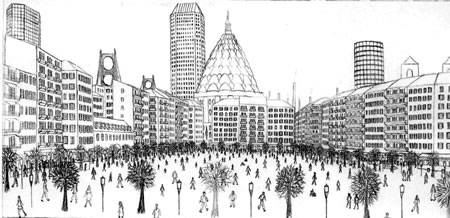

Trehin's renderings and texts show a detachment from the lives of the citizens of Urville, with key individuals given no backstory, and on the perspective images, people are almost always alone. As Charlotte Moore notes in her recent Guardian article:

"Yet the drawings are curiously timeless, swept clean of the detritus of human lives. The Lowryesque figures add visual rhythm but no sense of character. Gilles isn't interested in the personalities of his imaginary people. For him, history is about the emergence of civilisations through the impact of human activity. New York, which he also loves for its skyscrapers, is an especially fascinating example."

But Trehin is not alone, locked inside his own mind and creation, instead cozily cooped up with girlfriend, Catherine Mouet, an artist diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome.

From the Guardian piece:

"I'm intrigued by Catherine's role in Gilles' life: it's rare for an autistic person to form a long-lasting and satisfactory relationship. I can't imagine my sons being capable of it. Catherine is tiny and pretty; she's 35, but looks 20. Five years ago she discovered that she had Asperger's syndrome, a variant of autism. She says that the diagnosis was a relief. "It enabled me to understand what I've lived previous." (Her English isn't fluent, but it's better than my French.) Meeting Gilles, she says, was the best thing that ever happened to her. Communication between them is "easy, simple, without hidden meanings or ambiguities. We are not identical, but we are complementing each other."

It's hard not to be envious of this fascinating couple, locked into their own domestic bliss, with few distractions, and each with a fantasy world to retreat to. Who wouldn't want to live in Urville?

[First posted May 10, 2006]