Two news items aroused my disurbanist instincts last week, and in my paranoid modus operandi where everything is connected, thought that they represented two aspects of an identical process: the continued fragmentation and mutation of the urban condition.

Firstly, in a great article in The Atlantic, entitled "Gentrification and its Discontents" Benjamin Schwarz reviews two recent books, Naked City by Sharon Zukin and Twenty Minutes in Manhattan by Michael Sorkin, looking at life in New York, each in part bemoaning the "Disneyification' of Greenwich Village. With the full title of "Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places", it's not hard to guess where the jumping off point is for the Zukin book. Schwarz considers both books to be consciously in a dialogue with Jane Jacobs, the doyenne of urban writing ever since her 1961 book Death and Life of Great American Cities, and compares their relative positions.

(Image showing Greenwich Village if Robert Moses plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway had been built, by Vanshnookraggen)

What has come to pass in Greenwich Village? The vibrant mixed-use community that Jane Jacobs wrote about so affectionately and campaigned to save from the tyranny of Robert Moses has, lo-and-behold, turned into a kind of bo-ho theme park, in the process losing its soul, or 'authenticity' as Sharon Zukin would have it. I'm sure the same thing applies to other renowned neighbourhoods in great cities across the world - Haight-Ashbury in SF springs to mind, and here in London Carnaby Street, Portobello Road and much of Notting Hill are pale shadows of what made them unique in the first place.

But what does 'authentic' mean in this context? Schwarz argues convincingly that the Greenwich Village that Jane Jacobs depicted in the most oft-recalled part of DALOGAC was at a transitional point between the old industrial usage and a largely residential usage, under the forces of gentrification, and that what Zukin wants is for the city to remain in this transitional zone, forever teetering on the cusp of the future. It's a nostalgic, highly sentimental view and one that Jane Jacobs writing is also guilty of. She observed a city that was already changing, and presented a series of matronising, personal opinions as an indisputable analysis of what makes cities work.

We know where this leads. Jacobs founded a powerful myth of urbanism, that the sine qua non of urban form was to found in the 'ballet of Hudson Street', and with it created such as narrow definition of what represents vitality in cities that it can only be achieved with the values that Jacobs proscribed, and that conversely, anything that ignores any of these principles must be doomed to failure. The New Urbanists have taken a set of observations from Death and Life of Great American Cities, and turned them into design guidelines, a form of environmental determinism that in many ways is the exact opposite of what Jacobs wrote and stood for. The Death and Life of Great American Cities is a compelling read, but it is deeply flawed book.

Such a narrow depth of field seems increasingly less relevant in today's globalised economy and accelerated culture. The forces of gentrification move ever faster. The city districts that Jacobs wrote about so evocatively/cringingely can now be seen as a mirage, or at least a frozen moment in the evolution of a neighbourhood. Even New York, arguably the definitive city of the 20th Century, seems increasingly irrelevant as the hothouse for urbanism for the 21st Century. For this we need to look beyond Greenwich Village, outside the western cities of Europe and the US, and look at Asia and South America. Jane Jacobs principles seem increasingly irrelevant to the raging economic and urbanising forces at work in say Shanghai, Dubai or Sao Paulo.

The urban landscape of 21st Century China is not somewhere that a 1960's treatise on diverse, walkable neighbourhoods in the US has much relevance. The forces of globalisation, and the transformation of Chinese society under Deng Xioping's plans for economic reform have led to the situation where almost all goods are manufactured in China, and unprecedented urban growth in Special Economic Zones (SEZ) such as Shenzhen and across the Guangdong province.

China has become literally the workshop of the world. In parts of the Shenzhen SEZ, giant manufacturing complexes represent a new set of local urban conditions, factory cities on a vast scale. Many employ hundreds of thousands of migrant workers who have travelled in from rural areas to try and earn money for their families, living and working in tightly controlled and highly regimented communities

Recently the news has been full of stories about working conditions at the Taiwanese owned manufacturing corporation Foxconn, anchored by the Hon Hai Precision Industry Co, an electronics assembly firm building computer and electronics hardware for US and Japanese owned corporations like Dell, HP, Microsoft, Sony and most notably Apple 1. In the past 6 months alone, 10 Foxconn employees have committed suicide, leading to an increased scrutiny in the West to the living and working conditions inside these factory cities.

Foxconn's walled Shenzhen factory complex, the Longhua Science & Technology Park, is a citadel, within a city within a megalopolis of 14 million people and growing. The Daily Mail dubbed it iPod City back in 2006 - since then its size has nearly doubled. Here Foxconn employs over 420,000 people - more than the population of Bristol (in fact there are only 9 cities in the UK with more people). With such a large migrant workforce, lacking residency permits (hukou), most employees live in company owned dormitories, and travel to work on company buses. The streets, buidlings and infrastructure are all Foxconn built and owned. Yet there are few good intentions on the pavements of Foxconn city, no Cadbury Brothers or Titus Salt looking to build model communities for their workers. A soft blend of commerce and utopian socialism has been replaced with a schizoid mix of global capitalism and hardline Communism.

In a satirical piece, IT journalist Dan Lyons [who publishes online under the moniker Fake Steve Jobs] writes:

"But the Foxconn people all work for the same company, in the same place, and they’re all doing it in the same way, and that way happens to be a gruesome, public way that makes a spectacle of their death. They’re not pill-takers or wrist-slitters or hangers. They’re not Sylvia Plath wannabes, sealing off the kitchen and quietly sticking their head in the oven. They’re jumpers. And jumpers, my friends, are a different breed. Ask any cop or shrink who deals with this stuff. Jumpers want to make a statement. Jumpers are trying to tell you something."

As an act of architectural performance, Foxconn's suicide jumpers are every bit as profound as Jacobs' ballet of the sidewalk. Foxconn's intial responses were architectonic - to put up safety nets; and spatial - to increase rooftop security patrols, before starting to address pay and working patterns.

Can we begin to understand life in iPod City? Can we even comprehend what it is to live and work here, let alone began any comprehensive understanding of what constitutes urbanism or streetlife here?

In addition to its dozens of assembly lines and dormitories, Longhua has a fire brigade, hospital and employee swimming pool, where Mr. Gou (the founder of Hon Hai) does early morning laps when he is there. Restaurants, banks, a grocery store and an Internet cafe line the company town's main drag. More than 500 monitors around the campus show exercise programs, worker-safety videos and company news produced by the in-house television network, Foxconn TV. Even the plant's manhole covers are stamped "Foxconn."

(Images of Foxconn found here)

Guangdong Province and Gotham, Shenzhen and SoHo, are locked in a symbiotic relationship of economies and cultures. If Manhattan was a laboratory of the urban condition during the 20th Century, it is Shenzhen which is the petri dish of 21st century urbanism. The key to understanding the urbanism of Chinese factory cities, isn't to be found in any book by Jane Jacobs.

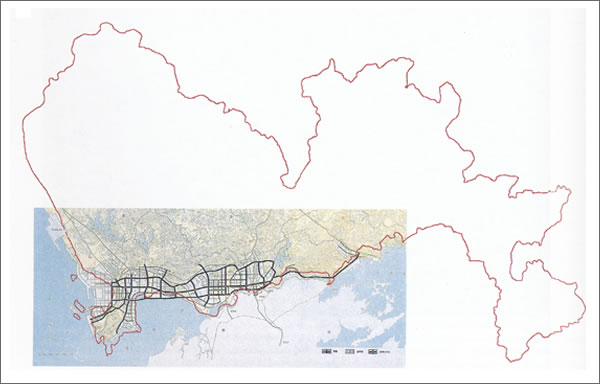

Some of the most insightful analysis of the urban forces in Shenzhen are to be found in Great Leap Forward: Project on the City 1, by Harvard Design School, and co-edited by Rem Koolhaas. It carries all of the hallmarks of OMA's analytical investigations into emerging urban conditions, and as part of a wider investigation into the Pearl River Delta region of China, explores the origins of the inherent contradictory nature of the Shenzhen SEZ, analysed as a linear city:

"'Three Paths and One Leveling,' the slogan that inaugurated the construction of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, delineates the formula of a minimally yet ambitiously planned city. Along with the necessary erasure - the preparatory 'leveling - Shenzhen is shaped as a LINEAR CITY. Between its first (1982) and second (1984) master plans, the Shenzhen SEZ was laid out as a linear instrument for organising the flow of capital. Although stretching 50 kilometers along the border with Hong Kong, its layout numbers only three east-west avenues (the 'three paths') and twelve north-south cross connections. It is precisely the scarcity of connections and the freedom from a preestablished pedestrian'grid' that forms the basis for all future urban incarnations. Distilled into an 'essential' traffic pattern, the plan of the zone underscores the INFRARED redefinition of the city as infrastructure. Recognizing that Hong Kong owes its prosperity to its infrastructures - container ports, tunnels, bridges, and highways connecting the harbor with the New Territories ( a warehouse hinterland storing containers and people alike) - the Shenzhen SEZ advertises itself as a colossal infrastructure, and link between the financial incentives of the socialist market economy and international capital flowing out of Hong Kong."

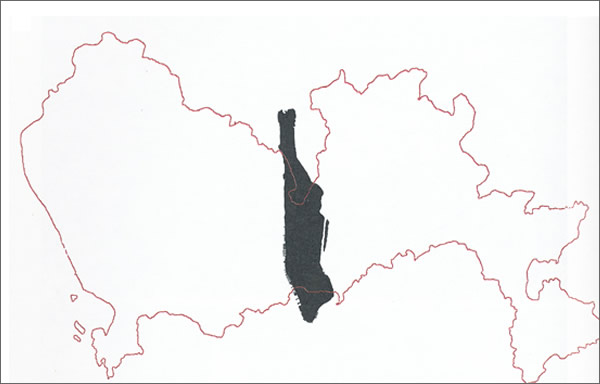

(Images from Great Leap Forward, showing, from top, Shenzhen SEZ compared to Manhattan, traffic plan of Shenzhen SEZ, the 1982 masterplan, the 1984 masterplan, the 1996 masterplan.)

But the book seldom comes down from the macroscopic view to look at life at street-level in Shenzen. This post at Polis blog shows that within the explosive growth of the Shenzhen megapolis are engulfed and assimilated a number of smaller villages. These Villages in the City are to Shenzhen as Greenwich Village was to New York - perhaps a Chinese Jane Jacobs will emerge to champion their unique qualities, but it is more likely they will eventually be swept away on the unstoppable tide of progress and Five Year Plans.

Schizophrenic Shenzhen has replaced Delirious New York.

- I say most notably because it always the Apple connection that attracts the press headlines. Part of this is due to pure linkbait - publishers know that mention of Apple leads to more eyeballs and web links. But I think that the press love to explore the dichotomy or the irony (and possibly the schadenfreude) - that those lustful consumer electronics products (of which the iPod, iPhone and iPad are perhaps the most visible examples) we enjoy in our western homes or Greenwich Village coffee shops could be the product of a toxic workplace, unsavory working practices and inhumane living conditions. That products presented as liberating pieces of lifestyle tech come from one of the most secretive, regimented and restrictive working environments is a delicious, tempting irony few hacks can resist.